June 01, 2015

June 01, 2015

MUSIC USED AS RESISTANCE TO THE NAZIS CAPTURES NEW AUDIENCES

By MATT LEBOVIC

A performance of ‘Defiant Requiem: Verdi at Terezin’ at Boston’s Symphony Hall on April 27, 2015. Originally led by conductor Raphael Schachter, 150 Terezin inmates learned Verdi’s Requiem mass by rote, and performed it sixteen times. (photo credit: Michael J. Lutch)

BOSTON – It might be hearing the survivors’ haunting voices, singing Yiddish songs recorded after the Holocaust, or maybe it’s listening to romantic songs from the “cabaret” at Westerbork, where Jews awaited weekly transports to death.

With many back-stories to choose from, a new wave of researchers and artists is elevating “music as resistance” to the forefront of Holocaust education. A leading project is the traveling mega-production called “Defiant Requiem: Verdi at Terezin,” a memorial concert for the musical prisoners of the Nazi camp Theresienstadt, also known as Terezin, outside Prague.

Launched in 2002, the production hinges on a lavish, full orchestra performance of Giuseppe Verdi’s seminal Requiem, a Roman Catholic funeral mass. It was this complex Latin arrangement that Jewish conductor Raphael Schachter, imprisoned in Theresienstadt, chose to perform with a chorus of 150 fellow prisoners in 1943.

To build their story around the 84-minute Verdi masterpiece, “Defiant Requiem” creators interspersed it with live narration, video testimony from Theresienstadt survivors, and “show” footage shot by Nazis inside the camp. The finished product has been performed more than 30 times around the world, and recently wrapped a coast-to-coast US tour.

In the so-called “camp-ghetto” Theresienstadt, the Nazis imprisoned thousands of Jewish artists and intellectuals, recognizing that murdering prominent Jews known abroad could backfire on the regime. This high concentration of creative inmates, combined with a rare degree of cultural self- autonomy, made Theresienstadt a productive site for spiritual resistance.

During the course of the camp’s existence, more than 2,300 lectures were given by 530 inmates, and 1,200 concerts performed. The communal library housed 60,000 volumes from all over Europe, and children created some of the Shoah’s best-known art.

A scene from the Nazi propaganda film, ‘The Fuhrer Gives the Jews a City,’ staged inside the Theresienstadt ‘camp-ghetto.’ This scene depicts the allegedly idyllic life of the camp’s children. (photo courtesy: National Center for Jewish Film)

Despite starvation and rampant illness, Schachter — known as Rafi — trained dozens of fellow inmates to perform Verdi’s Requiem on sixteen occasions. There was only one score to go around, smuggled in by Schachter, so he taught the choir by rote. The inmate choir was always hungry, not to mention exhausted from forced labor; many were ill.

As Schachter’s barracks mate and co-conspirator in music, Edgar Krasa sang bass in the choir of all sixteen performances. Toward the end of the camp’s existence, both men were deported to Auschwitz, after which Schachter died in a death march.

In 1994, half a century after the choir’s final performance, Krasa met conductor and maestro Murry Sidlin, who was interested in learning about Schachter. Sidlin took eight years to mix Krasa’s story with other testimony and clips to create “Defiant Requiem,” his multimedia magnum opus to Schachter’s accomplishments.

Krasa, now 94 and living in Newton, outside Boston, also shared his story with author Susie Davidson, who penned a 2012 book called, “The Music Man of Terezin,” based on Schachter’s activities at Theresienstadt. At the end of April, Davidson attended the Boston premiere of “Defiant Requiem,” where Krasa – who named his first son Rafi — was also in attendance.

According to Davidson, the production hints at psychological battles that were at play in the camp, as well as within the minds of prisoners like Krasa.

“Rafi Schachter made the prisoners feel they had some element of control over their circumstances, and that they weren’t just puppets waiting to be brought to their deaths,” said Davidson in an interview with The Times of Israel.

“Schachter took the prisoners from despondency of their fate to direct action and participation, and this gave them a lot of strength and some power,” she said. “He gave them a choice.”

Having written several books about the Holocaust, Davidson is particularly drawn to spiritual resistance, both as practiced during the genocide and by survivors and their descendants, she said.

“People are always going to create, even when they are confronted with the most terrible situations that life deals out, they will still react, and they still have humanity,” said Davidson.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Theresienstadt’s Council of Jewish Elders — nominally in charge of the ghetto — was vehemently opposed to Schachter’s productions. Not only were Jews performing a Catholic funeral mass, but it was possible the camp’s Nazi rulers would see an act of defiance and deport the entire cast. It was also said that by performing their own funeral mass, the Jewish prisoners were “apologizing for existing.”

The only known photo of Theresienstadt inmates performing Verdi’s Requiem Mass, taken during the final performance on June 23, 1944. Raphael ‘Rafi’ Schachter is seen conducting the choir, with Adolf Eichmann and an International Red Cross delegation in the audience (courtesy: The Terezin Foundation)

To end the debate, Schachter offered each performer the opportunity to bow out of the production, but not one of them did so. After performing the Requiem fifteen times to enraptured audiences, the inmate choir gathered for what would be its final performance on June 23, 1944.

Seated in the front row was Adolf Eichmann, a key architect of the Holocaust’s logistics, and other SS officials. A Red Cross delegation was also in attendance, as part of its mission to vet the camp for signs of genocide. If only in the minds of the imprisoned choir members, Verdi’s funeral mass was used to condemn the Nazi perpetrators watching their Jewish victims perform.

As Schachter most famously told his choir, “We will sing to the Nazis what we cannot say to them.”

Or, as said half a century later by “Defiant Requiem” creator Sidlin,“if you read the [Requiem’s] text as a prisoner, not as a Catholic, then the secret comes out as to why they did it.”

Music has long been associated with the Shoah, but often as a tool of deception used by Nazis to — for instance — lull Jews into submission at the death camps, or for its role in radicalizing the German public. When Jews appear as musicians, they are often under duress — performing to save their lives.

As researchers expand what’s meant by “resistance,” educators are increasingly turning to music as a platform to teach about genocide. In mainstream culture, films like “The Pianist” and “A Beautiful Life” used music and victims’ creative perspectives to make the Holocaust palatable for audiences. In 2012, “Defiant Requiem” was turned into a documentary, with Bebe Neuwirth narrating.

Though few recordings of musical performances during the Holocaust exist, historians have found ways to bridge the gap. Last month, part of a collection of 1,000 songs performed by Holocaust survivors in 1948 was released online by the Center for Traditional Music and Dance.

Recorded by amateur folklorist Ben Stonehill in a New York City hotel lobby, the songs include lullabies, blessings, and laments. Until being acquired by the US Holocaust Memorial Museum in 2006, the collection had been inaccessible to all but the most devout researchers.

An image of the Terezin concentration camp entrance in German-occupied Czechoslovakia, with a sign reading ‘Arbeit Macht Frei,’ is projected on a screen during a performance of Giuseppe Verdi’s Requiem Mass at St. Vitus Cathedral in Prague, Czech Republic on Thursday, June 6, 2013. (photo credit: AP Photo/CTK, Stanislav Zbynek)

Earlier this year, the Steven Spielberg-founded USC Shoah Foundation — responsible for recording testimony of more than 52,000 eye-witnesses — put out a call to scholars for a two-day October conference, “Singing in the Lion’s Mouth: Music as Resistance to Genocide.” In addition to exploring the role of music in the Holocaust, case-studies from the Armenian and Indonesian genocides will be presented.

Another current project is the Terezin Music Foundation’s year of “Liberarte,” through which new Shoah-related music commissions will be performed at Prague’s Spanish Synagogue and Boston’s Symphony Hall. The foundation will also publish a poetry anthology this year, featuring “new works on freedom” by 63 top international poets.

But one of the most celebrated case-studies of prisoners using music to bolster morale took place at the Dutch transit camp Westerbork, where inmates staged a lavish, weekly cabaret during the peak of transports to Auschwitz and Sobibor.

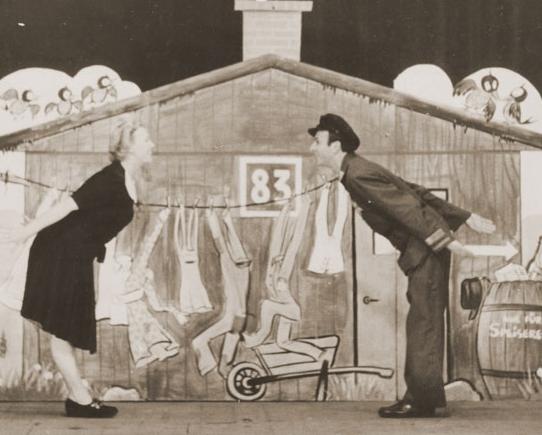

A scene from the Westerbork ‘cabaret,’ a weekly performance put on in the Dutch transit camp by some of the Netherlands and Germany’s top Jewish performers. Each week before the Tuesday night cabaret, a transport with 1,000 victims left for Nazi death camps in Poland. (courtesy: Yad Vashem Archive)

Organized by German theater director Max Ehrlich, the 18-skit performance poked fun at daily life in Westerbork, where every Tuesday a train took 1,000 inmates to their deaths in Poland. The production shut down shortly before Anne Frank and her family arrived at Westerbork, in August 1944.

To modern ears, an original recording of the bouncy love song, “Westerbork Serenade,” performed and written in the camp, may reverberate as gallows humor. However, according to Westerbork cabaret scholar Hinda Tzivia Eisen, this reading ignores the desperate context in which the songs were written.

“From a place of darkness, this music and comedy brought light,” said Eisen during a lecture on Westerbork, held at Boston’s Northeastern University last year. “When all you see around you is barracks and train track, perhaps it’s nice to imagine there could even be love there,” she said.