Michael Gruenbaum

(1930-2023)

Terezín survivor Michael Gruenbaum with the teddy bear that saved his life.

Terezín survivor Michael Gruenbaum with the teddy bear that saved his life. (Photo credit: Dennis Darling/Courtesy of Michael Gruenbaum)

A Life Profile

BY GAIL WEIN

Michael Gruenbaum says that one of the main lessons he has learned in life is to never take no for an answer. The man has a determination that is often fueled by proving and succeeding at what others think is impossible. Michael has demonstrated this over and over again: from an astonishingly rapid path to academic success (graduating from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology just eight years after being liberated from the Nazi concentration camp at Terezín), to finding a publisher for his autobiographical book after scores of rejections.

Imprisoned from 1942–1945 while still a young teenager, Michael Gruenbaum is a survivor of the Terezín Concentration Camp in what is now the Czech Republic. But there are many other facets to his life beyond being a survivor of the Holocaust — father, grandfather, husband, engineer, entrepreneur, scholar, and author.

Michael’s especially vivid memories of his time at Terezín are brought to life in his book for young adults, Somewhere There Is Still a Sun: A Memoir of the Holocaust (written with Todd Hasak-Lowy). He was inspired to write this book by his mother’s meticulously kept scrapbook which contained ephemera and memorabilia of the family’s imprisonment at Terezín. “Transport numbers, bank statements, ticket stubs, she collected it all,” he said.

Michael inherited the album after his mother passed away, and he decided to donate it to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC. The museum’s overwhelming enthusiasm over receiving such a rich collection of artifacts rubbed off on him, and he decided to write a book about his experiences for children. After mailing letters to 80 literary agents with no positive responses, he spent over two years reaching out to publishers. Finally, an editor from Simon and Schuster showed interest and paired him with a professional writer, Todd Hasak-Lowy. After the successful launch of the book that they created together, Michael set about to the task of getting it translated. Again, he doggedly contacted publishers in various countries until he received positive responses. The book is now available in 13 languages, including German, Czech, French, Russian, Greek and, most recently, Spanish. Michael’s book is a companion to his late wife Thelma’s book entitled Nešarim: Child Survivors of Terezín, published in 2004.

Early Years in Prague

Michael Gruenbaum was born in 1930 and was raised in a residential area of Prague. He went to Czech schools, and both he and his sister, Marietta, four years his senior, spoke Czech with their father and German with their mother. “I was always very interested in sports, especially soccer,” said Michael. “I remember cuddling in bed with my parents on Sunday mornings. I read the sports section while my parents read about the latest political developments.”

Michael’s father was a prominent attorney who worked for one of the richest families in Czechoslovakia. He describes his mother as a “socialite.” They led an affluent lifestyle, with a governess, a cook, and their own car — a rarity in those times.

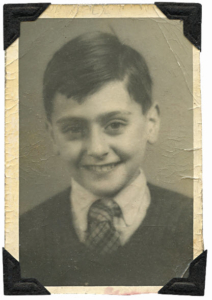

Michael Gruenbaum at age six. (Courtesy of Michael Gruenbaum)

Both his father and grandfather were observant Jews and had seats in the Old-New Synagogue in Prague. “My father was very active in the Prague Jewish community and tried to improve the life of Jewish people all over Czechoslo-vakia. My grandfather lived in a town a couple of hours north of Prague and he did not come to Prague very often. As a result, I occupied his seat [at the Synagogue] most of the time. My father and I walked together for 20 minutes Friday evenings and Saturday mornings because he wouldn’t drive or take the streetcar on the Sabbath. That for me was the best part of attending the services. My father spent a lot of his work traveling, so we didn’t see him that much.”

Sometimes on the weekends, the family traveled in their car to visit Michael’s grandparents in the countryside. “We used to like going hiking and collecting little silver emblems of each mountain which we fastened to our canes and then proudly displayed. And, on the way, we also collected mushrooms,” said Michael.

1939: The Nazis Take Over

On March 15, 1939, when the Nazis marched into Prague and took it over, Michael was nine years old. He has an especially vivid memory of that day. His father was abroad on a business trip and his mother was very worried. “I was sitting in a window and I watched this couple across the street on a roof holding hands, and they jumped off and committed suicide. That was a bad sign of all the things that were coming. Think about it. Why did they do that? What did they see ahead that we didn’t? That was really a terrible experience for me.”

The Nazis levied restriction upon restriction; the list grew every day. “The first thing we had to do was move from our large apartment in a section of Prague where we lived in great comfort,” said Michael. The family had to give up their car, their cook, and their governess and move to a much smaller apartment in the Prague ghetto.

Not only were their living conditions restricted, but there were many other edicts. Michael rattled off a long list of the increasing repression of the Jews in Prague: “We had to turn in the car. We had to turn in jewelry, oriental rugs, valuable books, artwork, radios, skis, bicycles, musical instruments, and so on. Anything of any value had to be turned in under the threat of death. We had to wear the yellow star; therefore, whenever I dared to go out on the street, I was chased by gangs of boys who were pelting me with stones. I had to zigzag from building to building to try to avoid them. We were not allowed to attend the public school and so I lost six years of formal schooling. We were not allowed to play in parks or attend concerts, movies, or the theater. We had to sit in the back of the streetcars; we were not allowed to travel outside of Prague. We were not allowed to associate with any non-Jewish friends. All our bank accounts were confiscated and our parents were not allowed to work. We were allowed to purchase only certain groceries and those were allowed to be bought only on certain days, and at certain times of those days. This was a dreadful and humiliating period in our lives.”

In 1941, Michael’s father was arrested by the Gestapo and interrogated and tortured for helping his bosses transfer their wealth to England before the Nazis came. The family never saw him again because he was murdered shortly after his arrest. Despite Karl Gruenbaum’s murder, his good standing in the Jewish community helped the family immensely later on as they were able to call in favors to avoid deportation while they were at Terezín.

Ousted from Prague

In November 1942, Michael, his mother, and his sister had to pack their suitcases and were sent to Terezín, where they remained until its liberation in 1945. They were permitted to bring a limited number of belongings. “We had to walk from the ghetto, and carry whatever we could carry. That was an extreme downsizing,” he said. While walking through their old neighborhood to the Exhibition Hall that the Germans used as an assembly area for those about to be deported, they spotted two familiar faces. “I noticed somebody was waving at us, it was our former governess. She was very sad to see us go. Whereas before that we saw that the cook, who immediately crossed to the other side of the street so she wouldn’t have anything to do with us because she was not allowed to associate with Jewish people. So, here the governess, who really sort of raised us, she had a strong attachment to us, so she waved to us and could care less about being arrested for that.”

Michael says he thought going to the camp might be better than living in Prague at that point, with all those many restrictions levied. “I was happy to get the opportunity to go somewhere else, because the situation really was pretty bad in Prague. My mom and I couldn’t imagine that going anywhere else would be much worse.”

They were at the assembly area for three days and nights; sleeping on thin mattresses on the floor, shoulder to shoulder and head to toe with many others, with little provided in the way of food and water. Michael was profoundly disturbed by the horrific sight of a man who was hungry, distraught, and perhaps demented. “I remember watching a cretin eating his own excretions, because he was so hungry. It’s one of those things you don’t forget.”

Arriving to Terezín

The family, along with many others, were put on a passenger train to Terezín. Upon arrival, Michael was separated from his mother and sister, and put in a dormitory room with about 40 other boys. Most, like Michael, were around 11 or 12. Each of the children’s rooms at Terezín had a “Madrich” (Hebrew for “teacher”) who acted as a youth leader. In Room 7, where Michael was assigned, a 20-year old man from Brno, Francis Maier, was put in charge. Franta (as everyone called him) was a strict leader and a great one. “He had a fantastically difficult job. He had to be a real tough disciplinarian. He wanted to make sure that we didn’t get sick, so hygiene was very important. He had to really be on top of everything and prevent fighting in a room with 40 rambunctious boys. He had to keep parents at bay because they came in and wanted to know what was going on. How was their boy doing? He kept them away, because if you do something for one boy, you had to do it for all the others. So you have to be a diplomat and at the same time keep discipline everywhere.”

“On top of that, he tried to educate us, surreptitiously. At Terezín there were very famous professors. So once in a while he brought somebody in to give us a lecture about history, physics, or something like that. Of course we had to have somebody be a lookout, to make sure no Germans would come and find that out. He taught us a lot about music. We learned about canons [a piece in which the same melody is begun in different parts successively, so that the imitations overlap] and he had us sing in choruses.”

Franta strongly believed in Kommuna — working together as a team. And just like many teams, the boys in Room 7 came up with a name: they called themselves the Nešarim (the Eagles). “One of the things we did was we had a soccer team and we played against other rooms. I was on the team and did well; I even scored a goal one time with my head, which was a big deal.”

Reunion of the Nešarim at Terezín in 1992. (Photo credit: Thelma Gruenbaum)

Franta was sent to Auschwitz in October 1944 and subsequently survived a death march. After the war, he kept in touch with his charges, even though they had quickly scattered around the globe. After the communists were overthrown in 1989, the survivors of Room 7 held their first of five reunions in Prague. Michael adds, “The second and third generations now make arrangements to meet periodically — they have

become the best of friends even though they live on different continents. The last big reunion we had in 2008 was attended by 62 people — I always say that if Hitler knew about that he would be turning in his grave!”

Powerful Memories

Michael has many strong memories of his time at Terezín. One that stands out was the day of the “count.” According to Michael, “The Germans didn’t know how many people were really in the camp and they suspected that some had escaped. So, on a very rainy, cold November day, they made everybody go outside and stand there for hours. What amazed me was, the night before, even though there was a curfew, my mother walked several blocks and brought me a blanket because she knew it was going be bad weather. I mean, it was heroic, really. Several people died in that count. Some people fainted. They made us stand there for about 16 hours, without food or anything.”

Another time, Michael was in the infirmary with yellow fever. “Suddenly at 5:00 in the morning, I hear a noise. It was my best friend who was throwing stones at my window, waving to me because he was going on a transport and he just wanted to come and say goodbye. I’ll never forget that he did that.” Michael will also never forget the constant fear of being deported. On the positive side, he cherishes his memories of the camaraderie of the boys in Room 7.

Michael was also one of the performers in the production of the children’s opera Brundibár by Hans Krasa. He says he derived pure enjoyment from the rehearsals and performances. “There was a moment of freedom that we had. We didn’t have to wear the yellow star, for instance. We forgot all the bad things that were around us when we were singing, and all that we had to face every day. And [in the story], winning the battle over the bad guy presented a bit of hope. It was a joyful affair not only for the people who were singing, but also in the audience. The kids really enjoyed it.” Brundibár also turned out to be a family affair as Michael’s mother worked in the arts department at Terezín and helped create the sets for the show.

All told, there were 55 performances of Brundibár, one of which was seen by representatives of the International Committee of the Red Cross who had come to inspect the camp. On that day, Michael was one of the boys who was told to line up as cans of sardines were handed out. They were taught to say, ‘Sardines again, Uncle Rahm?’ — referring to the then commandant of the camp, Karl Rahm — “Of course, the minute the Red Cross left, they collected those sardine cans and we never saw them again, just like we never saw them before.”

According to Michael, just a few weeks after the Brundibár performances, in September and October 1944, the Germans realized that they were going to lose the war and thus there was no need for pretense anymore. “But they were determined to fulfil one of the Führer’s main goals, to annihilate all the European Jews,” he said. “So out of the thirty-five thousand prisoners in Terezín, about two thirds were sent to Auschwitz in 11 transports.”

“I have a little booklet of drawings and sayings by my friends. One of them in Room 7 made a little sketch of a train going from Terezín, going downhill to where he drew a sign saying Birkenau [one of the camps at Auschwitz]. He knew, somehow he knew, that if you were on a transport, it was bad news. I don’t know whether he knew that there were gas chambers there or not, but he knew that it was not good.”

Eluding Transport – Four Times

Michael’s mother also knew that being put on a transport was bad news. She and her sister-in-law had devised a code, one that wouldn’t easily be detected by the censors. “If one of them was sent away and had a chance to write a postcard, the agreement was, if the handwriting slanted upward, then it’s a better place. If the handwriting slanted down, then it’s a worse place. My aunt was sent away, and her postcard came saying that she arrived, everything was well, and the handwriting was down. My mother knew then that she had to do everything she could to keep us in Terezín. As soon as my aunt wrote that postcard, she was sent into the gas chamber.”

The family was put on the transport list four times, and they managed to elude being sent to the East four times. “The first three times was because my mother went to the people that were preparing the list and reminded them of all of the things that my father had done for the Jewish community. That was the main reason why we were pulled out. The final time, in October 1944, she realized that the people who were making the lists couldn’t help us — they were also shipped to Auschwitz.” So, the family was on the list for deportation.

Terezín survivor Michael Gruenbaum with the teddy bear that saved his life. (Photo credit: Dennis Darling/Courtesy of Michael Gruenbaum)

At the appointed time, Michael’s mother brought him and his sister to the assembly area. Their assigned transport numbers were higher than 1,350, which meant they were close to the end of the line of the 1,500 prisoners boarding the train. That gave Michael’s mother enough time to quickly run over to the arts department. “She found her boss, Jo Spier, a very famous Dutch painter, and she told him, ’The order that the German in charge of this department gave us to make teddy bears for his children for Christmas — tell him that it’s not going to get filled because I and my two children are being deported.’ Luckily, Mr. Spier found the SS man right away and told him. The SS man thought about it for a moment and finally said, ‘All right. Pull them out of the transport.’ So, my mother got something in writing and collected us and showed the man at the desk the little note and asked, can we leave now? And the man said, ‘No, you can’t leave. You have to go up to the second floor into one of the rooms up there and wait until the train leaves.’”

“So we trudged up the stairway carrying whatever we could carry. And we got upstairs and opened the door to the first room. It was completely filled. There was no space for us to sit down. So we go down the hallway, open the door to the second room. The same thing. There must have been about thirty-five people in each of those rooms. So we finally went to the third room, the last room. There was space there, and we were able to sit down. And so we wait and wait. We thought we would hear the train leave, but instead, we heard a big commotion — the German soldiers with their fierce dogs rushing up the stairs, yelling, ‘50 more, 50 more.’ They needed 50 more bodies because they didn’t have the 1,500 to fill the train. So they emptied everybody out of that first room and put them on the train. And then they went into the second room and collected half of those people. You can imagine the noise, a horrible feeling, people pleading for their lives. Luckily, they never came to the third room, and that’s why I’m here today.”

Michael and his mother and sister remained at Terezín until liberation. They were there when prisoners who had been shipped East returned after walking days and days without food, water, or rest. The returning prisoners were malnourished, sick, and almost dead. Michael and his friends did what they could to help them, though they couldn’t get too close because many had typhoid. “We recognized some of the people — we couldn’t believe what they looked like. Nine months ago, they looked like us. Now, sadly, they were half the size. There was a girl, Margolius, whom we all admired, who was working in the garden. She was the most beautiful girl we’d ever seen, and we couldn’t recognize her — she was just a skeleton.”

Liberation

On May 8, 1945, the Terezín Concentration Camp was liberated by the Russian Army. Finally, Michael was able to leave the place he had been confined to for nearly three years. He got a ride to Prague with a friend’s family, but his mother and sister had to stay behind for some weeks; quarantined because of typhoid.

A few days after she was liberated, Michael’s mother wrote a letter to a friend abroad. “We do not know yet how the future will shape up for us. None of our old friends are alive anymore. We do not know where we are going to live. Nothing! But somewhere in the world there is still a sun, mountains, the ocean, books, small clean apartments, and perhaps again the rebuilding of a new life.” Michael said, “She was a very optimistic woman. She did everything she could do to help us survive.”

Back in Prague, the family moved to a small apartment in their old building. They tried to get their possessions back. “A lot of the people really disappointed my mother because they claimed they never got [the possessions], or they didn’t want to return them for one reason or another. So, we got back only a very small amount.” Michael also returned to school, but was behind other students his age — having missed six years of formal education — and was put in a class for younger children.

“Not long after, my mother saw the handwriting on the wall and saw that the communists were going to take over the government. She just refused to live under another dictatorship, so she wrote to New York and asked to get visas for us to come to the United States.” The family was granted the visas, and they left Prague on April 11, 1948, two weeks after the communists took over.

From Prague to the United States

First, the family went to Paris for two months. Their number had not come up yet in the United States’ quota system, but they had to go somewhere. “The only place we could go at that time was Cuba. We had trouble getting transportation from Paris; every week my mother went to the travel agency and finally we ended up getting on an airplane to Havana.”

The family was in Havana for two years, and Michael was enrolled in an American high school. “I didn’t know a soul in Havana, of course. And so I was walking through the sidewalks in Havana with a little notebook, translating and trying to memorize idioms in Spanish and English from Czech. To the astonishment of the principal, I was able to finish all the requirements for graduation in two years. He couldn’t believe it.” Beyond academics, Michael was also a champion in ping-pong and in chess. In fact, he beat the math teacher in chess, even though the teacher was the odds-on favorite.

Michael graduated from that high school in 1950 and was honored at the graduation by the principal. Around the same time, the family’s quota number came up. “We left Havana on a freighter; we didn’t have any money to travel on a plane or anything like that. It took three days to get from the Havana port to the New York Harbor. When we arrived, we saw these all these little boats spewing water in the air. I said to my mother, ‘Isn’t that amazing — what a greeting they gave us!’ Well, it just happened to be July Fourth. So we got a good greeting, but we couldn’t get off the boat because nobody was there to process our papers.” Ultimately, Michael and his mother got an apartment in Elmhurst, Queens, and stayed there for a couple months.

“When I came to the United States, I had visions of becoming a professional soccer player. That was my goal. It didn’t happen that way. Because of my excelling at school in Cuba, the principal wrote me a fabulous recommendation to MIT [Massachusetts Institute of Technology]. Because I had the wind behind me, I finished MIT in three years instead of four.”

“It’s hard to imagine that just eight years after leaving Terezín, I was standing on the steps of MIT in Cambridge, with my cap and gown, next to my beaming mother, having graduated from that prestigious institution in a language I didn’t even speak eight years before. Who would have imagined that?”

Then, Michael was drafted into the army during the Korean War. Because of his acumen in languages, he was sent to Language School. But, once there, the Army insisted on a 3-year commitment, which Michael declined. So instead, he wound up in Washington, DC, as a draftsman for a unit planning parades and funerals.

Prior to being drafted, Michael spent six months in a training program for the Illinois Highway Department. While he was there, he reconnected with a high school friend who had moved from Cuba to Chicago. “She came to visit me and she brought this girl with her who was Jewish and who was really my type because she was very interested in children and in music. And we hit it off very well. As a result of life’s mysterious ways, a boy from Czechoslovakia ends up in Havana and later through a Cuban classmate, meets his future wife in Paris, Illinois. How romantic can you get, right?”

Returning to Boston

Terezín survivor Michael Gruenbaum speaks to the members of the Boston Children’s Chorus about his experience in a concentration camp after a rehearsal in Boston on Oct. 14, 2017. (Photo credit: John Tlumacki/The Boston Globe via Getty Images)

After Michael’s service in the Army, he returned to school, earning a master’s degree in urban planning at Yale University. In 1961, he accepted a job at the Boston Redevelopment Authority, and has been in Boston ever since. While at the BRA, he published a big book entitled Transportation Facts for the Boston Region, which became a best seller. He then worked for the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as the Special Assistant to the Commissioner of the Massachusetts Department of Public Works, and changed the state highway map to include not only roads but all modes of transportation, which the Federal Administrator in Washington then used to persuade all other states to do the same. “Afterwards I worked for a private company and at the end we formed, and I became a partner in, our own transportation planning and traffic engineering company, which we sold after 14 years. My wife, Thelma, also worked for the company and when we sold it, we both retired and started traveling all over the world.”

“Thelma and I were married for 50 years until she unfortunately succumbed to ALS. We have three sons: David, Peter, and Leon, all of whom have had successful careers; and four grandchildren. I still live in the house we bought 52 years ago where I plan to have a big, coronavirus-delayed party next summer to celebrate my 90th birthday. Considering all the obstacles at the very beginning, it’s quite an amazing achievement.”

Concluding Words

“People ask me, quite often, what did you gain from this whole experience? And I always say, two major things. One is don’t ever get married to your possessions. We lost our possessions about four times: first to the Nazis, then leaving Prague on the way to Terezín, then emigrating from Prague to Cuba, and then in New York City where our belongings got lost en route. Somehow, they can always be replaced, so just don’t worry about it. And the other thing is, don’t ever accept no for an answer. My mother was a prime example of that, and for that matter, even getting my book published is a prime example of that. You just have to keep trying and trying.”

“I had no intention of writing a book, but I’m very happy that I did. The fact of the matter is, out of the twelve boys that survived our room out of the 80 that passed through it, only three are still alive. I just feel a certain burden on me to let people know what happened and keep the Holocaust memory alive.”